Over the last week, I took advantage of the Christmas break to read Dilexit Nos (“He Loved Us”), an encyclical letter by Pope Francis that came out in October of this year. It is a meditation on devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

I was excited when it came out, because the Sacred Heart has been a favorite devotion of mine for a long time. I memorized a prayer of consecration to the Sacred Heart when I was 19 or 20 and it has stuck with me ever since. There was something that grabbed me about contemplating the heart of Jesus. It helped seal my Christian faith as a young adult confronted with a variety of challenges to religion and other existential crises that come with life in general and the college experience in particular.

You don’t have to be Catholic to benefit from devotion to the Sacred Heart. I wasn’t when I first adopted it. It is Protestant-friendly as far as I can tell.

The prayer I learned begins with, “I give myself and consecrate to the Sacred Heart of our Lord Jesus Christ, my person and my life, my actions, pains and sufferings, so that I may be unwilling to make use of any part of my being other than to honor, love and glorify the Sacred Heart.” And it goes on to request to remain always close to the heart of Jesus and to rely completely on his mercy.

The words and imagery struck me as very powerful, but before this latest reflection from Pope Francis, I had never really stopped to think consciously about what it means to adore, specifically, the heart of Jesus. The image of the heart is so charged with meaning in the popular mind that one just assumes its significance and connotations without thinking about it too much. I was vaguely aware of the apparitions of Jesus to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque in France in the 17th century that helped spur this particular form of the devotion, as well as those given to St. Faustina Kowalska in Poland in the 20th that resulted in the famous Divine Mercy chaplet, but the symbol of the heart of Jesus goes back much further, in fact, to Scripture itself, as Francis shows.

The most direct explanation of this devotion comes about midway through the encyclical, where Francis explains:

Devotion to the heart of Christ is not the veneration of a single organ apart from the Person of Jesus. What we contemplate and adore is the whole Jesus Christ, the Son of God made man, represented by an image that accentuates his heart. That heart of flesh is seen as the privileged sign of the inmost being of the incarnate Son and his love, both divine and human. More than any other part of his body, the heart of Jesus is “the natural sign and symbol of his boundless love.”

After describing the heart according to Greek literature as the “inmost part of human beings, animals and plants” through which “both the higher faculties and the passions were thought to pass,” Francis shows that the word in the Bible is used to mean “a core that lies hidden beneath all outward appearances, even beneath the superficial thoughts that can lead us astray.” It is “the locus of sincerity, where deceit and disguise have no place” and is “the basis for any sound life project.” Thus, “the Word of God is living and active... it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Hebrews 4:12).

Pope Francis says a recovery of cultivating our own hearts can help to make sense out of our lives, just as Mary “treasured all these things and pondered them in her heart” (Luke 2:19 and 51), especially the things she did not immediately understand.

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus appeals to the heart of the people he encounters and sees their heart, as in Matthew 9 where he tells both the paralytic and the woman with a hemorrhage to “take heart" and asks the scribes, “Why do you think evil in your hearts?”

Francis underlines the incarnational aspect of devotion to the Sacred Heart, the fact that Jesus became fully man while remaining fully God.

His heart, then, is not merely a symbol for some disembodied spiritual truth. In gazing upon the Lord’s heart, we contemplate a physical reality, his human flesh, which enables him to possess genuine human emotions and feelings, like ourselves, albeit fully transformed by his divine love.

This reality allows us, in Benedict XVI’s words, to “contemplate and encounter the infinite in the finite.” The incarnational character of devotion to the Sacred Heart is also trinitarian, because “[w]hen the Son became man,” Francis writes, “all the hopes and aspirations of his human heart were directed towards the Father” and showed a “complete and constant orientation towards him.” The Holy Spirit’s fire fills the heart of Christ, and the water that springs from his pierced side is likewise a sign of the Spirit.

The heart of Christ appears in Scripture primarily by way of his pierced side, out of which flowed blood and water. This was seen by the first Christians as a fulfillment of prophecies, such as those in Zechariah 12 and 13, that spoke of the Messiah as one who is pierced, opening a fountain of living waters.

I will pour out a spirit of compassion and supplication on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and they shall look on him whom they have pierced… On that day, a fountain shall be opened for the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, to cleanse them from sin and impurity. (Zech 12:10; 13:1)

Pope Francis explains:

One who is pierced, a flowing fountain, the outpouring of a spirit of compassion and supplication: the first Christians inevitably considered these promises fulfilled in the pierced side of Christ, the wellspring of new life. In the Gospel of John, we contemplate that fulfilment. From Jesus’ wounded side, the water of the Spirit poured forth: “One of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once blood and water flowed out” (Jn 19:34). The evangelist then recalls the prophecy that had spoken of a fountain opened in Jerusalem and the pierced one (Jn 19:37; cf. Zech 12:10). The open fountain is the wounded side of Christ.

After reviewing a number of other biblical passages related to the pierced side of Christ, Francis concludes, quoting St. John Paul II, “the essential elements of devotion [to the Sacred Heart] belong in a permanent fashion to the spirituality of the Church throughout her history; for since the beginning, the Church has looked to the heart of Christ pierced on the Cross.”

So while there may be various traditional forms of devotion to the Sacred Heart, such as those connected to particular saints and seers throughout history, the essence has been a part of Christian belief from the beginning. Francis admires at length, for example, the beautiful apparitions of Jesus to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, but he adds that “[w]e need not feel obliged to accept or appropriate every detail of her spiritual experience. [...] More important than any individual detail is the core of the message handed on to us.”

Pope Francis discusses the contributions of the Church Fathers to the devotion during the first few centuries, who “spoke of the wounded side of Jesus as the source of the water of the Holy Spirit: the word, its grace and the sacraments that communicate it. […] His wounded side, understood as his heart, filled with the Holy Spirit, comes to us as a flood of living water.”

He mentions the writings of Eusebius who spoke of martyrs being born from “the heavenly and eternal streams that flow from the heart of Christ,” St. Justin Martyr who said believers “have come forth from the heart of Christ,” and St. Ambrose who spoke of Christ as “the river whose streams gladden the city of God […] for from his side flows living water.”

St. Augustine saw in St. John the Apostle’s leaning on Jesus’ bosom “the symbol,” Francis says, “of our intimate union with Christ, the setting of an encounter of love. […] In effect, Augustine writes that John, the beloved disciple, reclining on Jesus’ bosom at the Last Supper, drew near to the secret place of wisdom.” It is the place we too can go in order to hear the beating heart of Jesus, to unite our hearts to his. Lines from one of my favorite hymns come to mind: “Ye that labor and are heavy laden, lean upon your dear Lord’s breast ... come and I will give you rest.” Francis quotes Benedict XVI: “All of us, when we pause in silence, need to feel not only the beating of our own heart, but deeper still, the beating of a trustworthy presence, perceptible with faith’s senses and yet much more real: the presence of Christ, the heart of the world.”

Moving on to the middle ages, the theme of Jesus’ heart appears in the writings of a number of figures, including St. Bernard of Clairvaux, William of Saint-Thierry and St. Bonaventure.

St. Bernard’s sermons on the Song of Songs are quoted: “A lance passed through his soul even to the region of his heart. No longer is he unable to take pity on my weakness. The wounds inflicted on his body have disclosed to us the secrets of his heart; they enable us to contemplate the great mystery of his compassion.”

William of Saint-Thierry: “Your heart, Jesus, is the sweet manna of your divinity that you hold within the golden jar of your soul (cf. Heb 9:4), and that surpasses all knowledge. Happy those who, having plunged into those depths, have been hidden by you in the recess of your heart.”

St. Bonaventure: “In order that from the side of Christ sleeping on the cross, the Church might be formed and the Scripture fulfilled that says: ‘They shall look upon him whom they pierced’, one of the soldiers struck him with a lance and opened his side. This was permitted by divine Providence so that, in the blood and water flowing from that wound, the price of our salvation might flow from the hidden wellspring of his heart.”

Francis gives an overview of several saints who developed the devotion, primarily behind the walls of the monasteries. He lists “a number of holy women,” such as St. Gertrude in the 13th century:

Saint Gertrude of Helfta, a Cistercian nun, tells of a time in prayer when she reclined her head on the heart of Christ and heard its beating. In a dialogue with Saint John the Evangelist, she asked him why he had not described in his Gospel what he experienced when he did the same. Gertrude concludes that “the sweet sound of those heartbeats has been reserved for modern times, so that, hearing them, our aging and lukewarm world may be renewed in the love of God”. Might we think that this is indeed a message for our own times, a summons to realize how our world has indeed “grown old”, and needs to perceive anew the message of Christ’s love?

Francis then reviews preachers and teachers who, later on, spread the devotion outside of the monasteries, one of the most famous being St. Francis de Sales: “In his writings, the saintly Doctor of the Church opposes a rigorous morality and a legalistic piety by presenting the heart of Jesus as a summons to complete trust in the mysterious working of his grace.” He emphasized a personal relationship with Jesus, who knows the number of hairs on our head and possesses a “most adorable and lovable heart […] on which all our names are written.”

Under these influences, St. Margaret Mary Alacoque experienced her visions of Jesus, who came to her to show “[m]y divine Heart […] so inflamed with love for men, and for you in particular, […] no longer able to contain in itself the flames of its ardent charity.” Her apparition, Francis says, “invites us to grow in our encounter with Christ, putting our trust completely in his love.”

In another apparition that occurred during adoration before the Eucharist, she relates:

Jesus appeared, resplendent in glory, with his five wounds that appeared as so many suns blazing forth from his sacred humanity, but above all from his adorable breast, which seemed a fiery furnace. Opening his robe, he revealed his most loving and lovable heart, which was the living source of those flames. Then it was that I discovered the ineffable wonders of his pure love, with which he loves men to the utmost, yet receives from them only ingratitude and indifference.

Francis cites Pope John Paul II, who said the influence of Margaret Mary was a response to an overly rigorous school of thought — “Jansenism” — that downplayed God’s mercy. Jesus gave her the “first Fridays” devotion — the practice of receiving communion on the first Friday of each month — and several promises associated with it, which “sent a powerful message,” Francis says, “at a time when many people had stopped receiving communion because they were no longer confident of God’s mercy and forgiveness and regarded communion as a kind of reward for the perfect.”

The “Jansenists” found this and other practices encouraged by the mystic “difficult to comprehend, for they looked askance on all that was human, affective and corporeal, and so viewed this devotion as distancing us from pure worship of the Most High God.” Francis continues reflecting on the significance of this for our own times:

It could be argued that today, in place of Jansenism, we find ourselves before a powerful wave of secularization that seeks to build a world free of God. In our societies, we are also seeing a proliferation of varied forms of religiosity that have nothing to do with a personal relationship with the God of love, but are new manifestations of a disembodied spirituality. I must warn that within the Church too, a baneful Jansenist dualism has re-emerged in new forms. This has gained renewed strength in recent decades, but it is a recrudescence of that Gnosticism which proved so great a spiritual threat in the early centuries of Christianity because it refused to acknowledge the reality of “the salvation of the flesh”. For this reason, I turn my gaze to the heart of Christ and I invite all of us to renew our devotion to it. I hope this will also appeal to today’s sensitivities and thus help us to confront the dualisms, old and new, to which this devotion offers an effective response.

St. Claude de La Colombière, Margaret Mary’s spiritual director in Paray-le-Monial, “immediately undertook her defence and began to spread word of the apparitions.” He contemplated her apparitions in his practice of the famous Spiritual Exercises developed by St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order to which he belonged. Francis says:

Some of the language of Saint Margaret Mary, if poorly understood, might suggest undue trust in our personal sacrifices and offerings. Saint Claude insists that contemplation of the heart of Jesus, when authentic, does not provoke self-complacency or a vain confidence in our own experiences or human efforts, but rather an ineffable abandonment in Christ that fills our life with peace, security and decision.

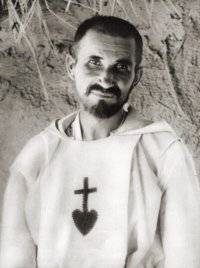

Moving on to the 19th century, Francis highlights the contributions of St. Charles de Foucauld and St. Therese of the Child Jesus (aka Therese of Lisieux), who gave devotion to the Sacred Heart “an even more evangelical spirit.”

Charles de Foucauld reverted to the faith largely under the influence of his cousin, Marie de Bondy, who also introduced him to devotion to the Sacred Heart. After becoming a missionary and priest in Africa and the Middle East, he signed all his letters “with the words Jesus Caritas separated by a heart surmounted by the cross.” Pope Francis shows where he spoke often of his devotion to the Sacred Heart in his correspondences with others. Charles wrote, “With all my strength I try to show and prove to these poor lost brethren that our religion is all charity, all fraternity, and that its emblem is a heart.”

Francis says:

On 6 June 1889, Charles consecrated himself to the Sacred Heart, in which he found a love without limits. He told Christ, “You have bestowed on me so many benefits, that it would appear ingratitude towards your heart not to believe that it is disposed to bestow on me every good, however great, and that your love and your generosity are boundless”.

St. Therese of Lisieux, a Discalced Carmelite nun in France in the late 1800s, wrote in her diary and letters about her devotion to the Sacred Heart, which freed her from a kind of spiritual or moral perfectionism, allowing her to depend totally on the mercy of God. In this way, her devotion “took on certain distinctive traits with regard to the customary piety of that age.”

She wrote in one of her letters, “You know that I myself do not see the Sacred Heart as everyone else. I think that the Heart of my Spouse is mine alone, just as mine is his alone, and I speak to him then in the solitude of this delightful heart to heart, while waiting to contemplate him one day face to face.”

Francis explains:

In many of her writings, Therese speaks of her struggle with forms of spirituality overly focused on human effort, on individual merit, on offering sacrifices and carrying out certain acts in order to “win heaven”. For her, “merit does not consist in doing or in giving much, but rather in receiving”. Let us read once again some of these deeply meaningful texts where she emphasizes this and presents it as a simple and rapid means of taking hold of the Lord “by his heart”.

He goes on to review writings in which the saint likens God to a mother or father who would not refuse to pardon their child who comes to them with sincerity. “I see that it is sufficient,” she writes, “to recognize one’s nothingness and to abandon oneself like a child into God’s arms.” Pope Francis says that “moralizers” who would not apply this to everyday people attempt “to keep a tight rein on God’s mercy” and remove “from the spirituality of Saint Therese its wonderful originality.”

After summarizing several more developments of devotion to the Sacred Heart throughout the last two centuries, Pope Francis says two specific characteristics emerge — compunction and consolation.

Compunction is “the honest acknowledgment of our bad habits, compulsions, attachments, weak faith, vain goals and, together with our actual sins, the failure of our hearts to respond to the Lord’s love and his plan for our lives.” But he adds that compunction is “not a feeling of guilt that makes us discouraged or obsessed with our unworthiness, but a beneficial ‘piercing’ that purifies and heals the heart.”

He says that recovering the practice of consoling the Sacred Heart of Jesus is a way to cultivate compunction. He refers to the method of prayer in which one attempts to be present to the suffering Jesus, to “experience it as a mystery which is not only recollected but becomes present to us by grace.”

Francis bases himself on Pope Pius XI’s 1928 encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor (“Most Merciful Redeemer”), who said that if “the soul of Jesus became sorrowful unto death” for future sins of humanity he foresaw, then he also saw our good deeds and acts of reparation “in order that his heart, oppressed with weariness and anguish, might find consolation.” Pius XI concludes “so even now, in a wondrous yet true manner, we can and ought to console that Most Sacred Heart, which is continually wounded by the sins of thankless men.”

Francis says:

Those words of Pius XI merit serious consideration. When Scripture states that believers who fail to live in accordance with their faith “are crucifying again the Son of God” (Heb 6:6), or when Paul, offering his sufferings for the sake of others, says that, “in my flesh I am completing what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions” (Col 1:24), or again, when Christ in his passion prays not only for his disciples at that time, but also for “those who will believe in me through their word” (Jn 17:20), all these statements challenge our usual way of thinking. They show us that it is not possible to sever the past completely from the present, however difficult our minds find this to grasp.

Pope Francis connects this practice of consoling the heart of Jesus to the mission it implies for all Christians to the world, “‘so that we may be able to console those who are in any affliction, with the consolation by which we ourselves are consoled by God’ (2 Cor 1:4).” He underlines the importance of works of mercy to the poor and suffering and the need to avoid proselytizing: “This dynamism of love has nothing to do with proselytism; the words of a lover do not disturb others, they do not make demands or oblige, they only lead others to marvel at such love.”

Related to the theme of service to others and mission, Pope Francis covers the social implications of devotion to the Sacred Heart, especially in the first and last chapters. In Chapter 1 he reflects on how retrieving even the idea of the human heart in general can help to give people in our “liquid” society a new center point for their fragmented lives.

Though no direct citation appears in the footnotes, the word “liquid” seems to be a reference to Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of “liquid modernity,” the idea that modern economies and technologies have fragmented the individual’s identity.

“We find ourselves,” Francis writes, “immersed in societies of serial consumers who live from day to day, dominated by the hectic pace and bombarded by technology, lacking in the patience needed to engage in the processes that an interior life by its very nature requires.”

He echoes these sentiments in the concluding paragraphs of the encyclical: “In a world where everything is bought and sold, people’s sense of their worth appears increasingly to depend on what they can accumulate with the power of money. […] The love of Christ has no place in this perverse mechanism, yet only that love can set us free.”

In the last chapter, he applies the concept of reparation for sins as a way to correct social injustices. “Amid the devastation wrought by evil, the heart of Christ desires that we cooperate with him in restoring goodness and beauty to our world.”

He says all sin is, to some degree, a social sin, and that when these accrue they can lead to what John Paul II called “structures of sin.”

“Frequently,” Francis explains, “this is part of a dominant mind-set that considers normal or reasonable what is merely selfishness and indifference.”

However:

Christian reparation cannot be understood simply as a congeries of external works, however indispensable and at times admirable they may be. These need a “mystique”, a soul, a meaning that grants them strength, drive and tireless creativity. They need the life, the fire and the light that radiate from the heart of Christ.

I have tried to give a few highlights of what stuck out to me over the last few days. While it was a lot to take in at once, I appreciated Francis’ deep dive on the writings of the saints and how devotion to the Sacred Heart developed over time. I don’t read encyclicals every time they come out, but there’s something about the Sacred Heart devotion that seems to … get to the heart of the matter. A reminder that Christianity is about the experience of the joy of being loved by the Lord, a simple truth that often seems hidden in everyday life under layers of complexity and strife. I’ll close with one last quote from the pope to this end:

The Second Vatican Council points out that “the ferment of the Gospel has aroused and continues to arouse in human hearts an unquenchable thirst for human dignity”. Yet to live in accordance with this dignity, it is not enough to know the Gospel or to carry out mechanically its demands. We need the help of God’s love. Let us turn, then, to the heart of Christ, that core of his being, which is a blazing furnace of divine and human love and the most sublime fulfilment to which humanity can aspire. There, in that heart, we truly come at last to know ourselves and we learn how to love.