It took me almost ten months, but I finally finished a great spiritual classic called The Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus1. It was a challenging read for me, not only because it’s old and written in a style that can seem haphazard to books I’m used to reading, but also because it constantly calls the reader to consider things that aren’t particularly joyful, including to remember death, to remember your sins, to forget the offenses of others and to check your evil intentions even when you are doing good deeds.

I say “the reader,” even though Climacus is writing primarily for other monks in the 7th century. But Pope Benedict XVI, in whose writings I first heard of Climacus, tells us in regards to the medieval monk’s text, “[W]e see that the monastic life is only a great symbol of baptismal life, of Christian life. It shows, so to speak, in capital letters what we write day after day in small letters.”2 In other words, there is something for us to gain from reading this kind of literature, even if we live in the world and do not practice such extreme fasting and prayer.

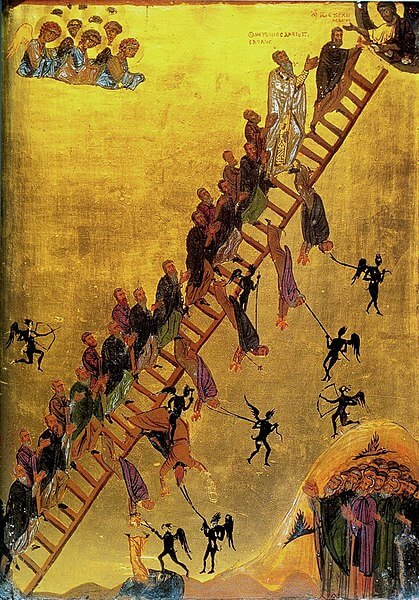

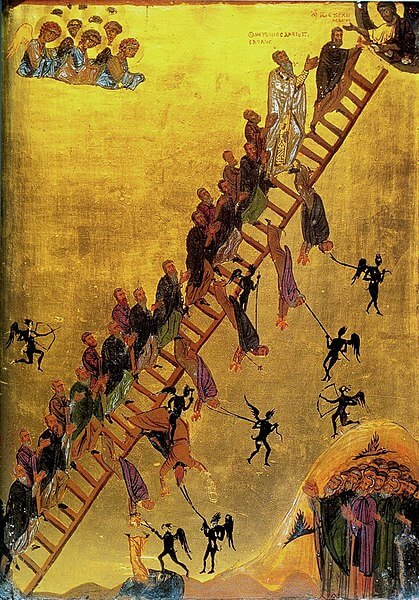

Again, The Ladder can be downright depressing. To illustrate the point, check out these little devils poking and prodding and otherwise making these poor souls miserable along the way of their divine ascent:

Notice how the good angels at the top are not really helping all that much, except by their thoughts and prayers. I’m not sure if it’s intended in this icon, but it reminds me that the evil of our days often seems far more real than the promises of heaven, even though we might know intellectually that the angels are there, quietly and invisibly aiding us. Pope Benedict says Climacus shows us that “we do not expect success in our earthly days but we look forward to the revelation of God himself at last.”

This can be a hard pill to swallow, because happiness is so often defined by lesser things, especially these days and in this first-world country. It’s what another St. John, the beloved apostle of Jesus, called “the pride of life” (1 John 2:16). I have this type of pride in abundance, so I know that it never ultimately satisfies. It is extremely difficult to turn mere intellectual knowledge of the promised hereafter into that more real and living knowledge called hope. I think that is why some people get so depressed, apart from whatever clinical reasons that exist. All of us, if we live long enough, find ourselves hanging on a precipice to an existential abyss and trying to claw our way back to safe ground by whatever shreds remain of our hope. The only option we have for any modicum of joy in this life is to hope in the next one, to hope in God. To whom shall we go but Him?

The Ladder takes you along that arduous journey from despair to hope, in 30 steps. One of the things that really stood out to me was the prominent role of forgiveness. Climacus often brings up the evil of “remembrance of wrongs” (47). If I had to add a subtitle to the book, it would be “The 30-Step Guide to Avoiding the Remembrance of Wrongs.” I would say this is the hardest challenge in the book, and I bet many people would agree with me.

Anyway, I took notes on this book while reading, which I will dump here with only minor edits, for anyone who might be interested. There are a lot of parts I came across that, in my modern mind, made no sense but that I kept in my notes anyway. If you read these notes with a bias against the ascetic traditions of Christianity, you will probably walk away even more confirmed in your bias.

The work frequently offers little observations that read a bit like proverbs, and a lot of what made it into these notes were just quotable quotes. I hope it’s representative of what each of the 30 steps is about, but fair warning: I got lazy. Nonetheless, I hope these amateur “Cliff notes” are beneficial in some way to anyone who may be interested in The Ladder.

Climacus defines different kinds of rational beings, naming angels God’s “friends” and men in relationship with God his “servants,” among many other grades of rational beings who are instead opposed to God. Among men are the “irreligious man” (atheist), “the lawless man” (heretic), “the Christian,” “the lover of God” and of good things, “the continent man” (celibate), and finally, “the monk,” (1) who withdraws from the world and “is a mourning soul that both asleep and awake is unceasingly occupied with the remembrance of death” (2).

There are three reasons for someone to withdraw from the world to become a monk: 1) “for the sake of the future Kingdom,” 2) “because of the multitude of their sins,” and 3) “for love of God” (2). Climacus says monks need “some Moses as a mediator” to lead them out of the Egypt of their sinful life and “rout the Amalek of the passions” (2). I think he is referring to a monk submitting to the abbot of a monastery.

To ascend to heaven requires violence to the body, fasting etc., because our mind is “a greedy kitchen dog addicted to barking” (2).

The good fight is hard and narrow, yet it is easy if we but “leap into the fire” (2).

All babes in Christ must begin with the virtues of innocence, fasting and temperance. Innocence means not sly or deceitful (3).

A firm beginning means that when you do falter, you can more easily lift yourself back up, as a bird may falter but stay afloat in its drift. If the soul loses its fervor, it must investigate the reasons why, because its fervor can only return through the same door it left (3).

Do not let your sins convince you to leave the monastic life, which is often an excuse to continue on in the very same sins (4). For unmarried men, things are easier because they have less business in the world, but married men are “bound hand and foot” (4).

However, Climacus gives advice to married men, who often live carelessly in the world:

Do all the good you can; do not speak evil of anyone; do not steal from anyone; do not lie to anyone; do not be arrogant towards anyone; do not hate any one; be sure you go to church; be compassionate to the needy; do not offend anyone; do not wreck another man’s domestic happiness; and be content with what your own wives can give you. If you behave in this way you will not be far from the Kingdom of Heaven. (4)

This is about the only thing Climacus writes directly for people living in the world. The rest of the book is almost exclusively directed to monks, although, as I have mentioned, there are still things to learn from it.

Make renunciations while you are still young, not buying the lie that you should relax or indulge so you don’t become weak. We reap the labours of our youth (4-5).

Monks may live 1) alone as a “spiritual athlete,” 2) “in silence with one or two others,” or 3) in a community, but Climacus says the second is suitable for many people (4).

A faithful monk is one “who has kept his fervour unabated, and to the end of his life has not ceased daily to add fire to fire, fervour to fervour, zeal to zeal, love to love” (5).

“The man who really loves the Lord” must hate the world, including money and even his own flesh, and expect all his help to come from heaven (5). A novice can be very fickle, committing the disgrace of always looking back (5). The novice may also think he must go back into the world to have the virtues of those he knows living in the world, but this is a temptation to false humility from the demons (6).

Let the dead bury their own dead, which Jesus taught, means let those spiritually dead (that is, people in the world) bury their physical dead (6). This seems to refer to monks’ injunction not to find an excuse in family affairs to leave the monastery.

Climacus heavily chastises monks who in the world made many ostentations to vigils and fasts, calling it a “sham asceticism” that is “watered by vainglory as by an underground sewage pipe” but soon withers “when transplanted to a desert soil” (6).

[T]he narrow way means: mortification of the stomach, all-night standing, water in moderation, short rations of bread, the purifying draught of dishonour, sneers, derision, insults, the cutting out of one’s own will, patience in annoyances, unmurmuring endurance of scorn, disregard of insults, and the habit, when wronged, of bearing it sturdily; when slandered, of not being indignant; when humiliated, not to be angry; when condemned, to be humble. Blessed are they who follow the way we have just described, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven. (6)

People in the world cannot do as mighty miracles as monks, because miracles are a reward they cannot receive, else “then what is the need of asceticism or solitude?” (7).

He speaks very harshly here about the need for monks to leave their earthly life behind, that their parents and family and friends really want their destruction if they cry and yearn for them to come back. He says it’s like Abraham leaving his kindred and father’s house, like Jesus when he said, “Who are my mother and brethren?” He says the monk should fight off grief for leaving family behind by mourning over his own death. Do not go back into the world even to convert sinners, for this is a temptation and trick of the devils. Also, many temptations are had in solitude, especially “the demon of wandering and of sensual desire” (8). “Detachment is excellent but her mother is exile” (8).

Let him be your father who is able and willing to labour with you in bearing the burden of your sins; and your mother–contrition, which can cleanse you from impurity; and your brother–your comrade who toils and fights side by side with you in your striving toward the heights. Acquire an inseparable wife–the remembrance of death. And let your beloved children be the sighs of your heart. Make your body your slave; and your friends, the Holy Powers (Angels) who can help you at the hour of your death, if they become your friends. This is the generation (family) of those who seek the Lord. (9)

Climacus ends this step with an aside on dreams and how they can be tricks from devils. For example, they being spirits can see ones relatives who are dying in a distant land, and revealing this in a dream to the credulous, they seem to foretell the future, which is impossible for them. If true angels reveal something to us in dreams, it is bound to be “torments, judgments and separations” (10), but even these can be from devils if they cause one to despair. Finding joy in dreams is something the inexperienced do.

Obedience is described as giving up responsibility for one’s actions to a superior, whether man or God, by obeying them unquestioningly. One cannot judge one’s superiors without taking on judgment to himself, and he is prideful if he thinks he knows what is best. “Those who submit themselves in the Lord in simplicity run the good race without provoking the bile of the demons against themselves by their inquisitiveness” (12).

He gives stories of when he lived among many wise elders in a monastery, and their rigour, including the advantage of public confession as a means to humility.

Story of Isidore, a monk who died early to join the Lord because of his complete obedience to his director.

Another story about a man named Laurence, a patient old monk who practiced full obedience to the abbot. He told Climacus, “But know this, Father, that if anyone surrenders himself to simplicity and voluntary innocence, then he no longer gives the devil either time or place to attack him” (15).

The director goes on to explain to Climacus that it is sometimes necessary to punish the innocent, so that they do not become vain and prideful.

He tells of a man named Abbacyrus who received maltreatment from the other monks but knew it was not in earnest, but rather to test him, which he heroically accepted so as to be tested by his “Fathers” rather than by devils (16).

He tells of Macedonius the archdeacon, who sought out punishment for the sake of humility, lowering himself in rank even in his old age. He tells Climacus, “Never […] have I felt in myself such relief from every conflict and such sweetness of divine light as now” (17).

An excerpt from conversations he had with one of the fathers he has been talking about:

At the gate of your heart place strict and unsleeping guards. Control your wandering mind in your distracted body. Amidst the actions and movements of your limbs, practise mental quiet (hesychia). And, most paradoxical of all, in the midst of commotion be unmoved in soul. Curb your tongue which rages to leap into arguments. Seventy times seven in the day wrestle with this tyrant. Fix your mind to your soul as to the wood of a cross to be struck like an anvil with blow upon blow of the hammers, to be mocked, abused, ridiculed and wronged, without being in the least crushed or broken, but continuing to be quite calm and immovable. (18)

Climacus goes on to say, “To admire the labours of the saints is good; to emulate them wins salvation; but to wish suddenly to imitate their life in every point is unreasonable and impossible” (19).

Part of remorse is doing violence to oneself.

He who will not accept a reproof, just or unjust, renounces his own salvation. But he who accepts it with an effort, or even without an effort, will soon receive the remission of his sins. (20)

Mourn for your brother’s sins.

He whose will and desire in conversation is to establish his own opinion, even though what he says is true, should recognize that he is sick with the devil’s disease. And if he behaves like this only in conversation with his equals, then perhaps the rebuke of his superiors may heal him. But if he acts in this way even with those who are greater and wiser than he, then his malady is humanly incurable. (20)

Don’t think your blessings or graces come from your own acts rather than your spiritual father’s. This is the danger for monks choosing to live the solitary life, which can bring pride.

Don’t blame others for your sins in confession.

At confession be like a condemned criminal in disposition and in outward appearance and in thought. Cast your eyes to the earth, and, if possible, sprinkle the feet of your judge and physician, as the feet of Christ, with your tears. (22)

Surrender to indignities.

That is why even John the Baptist required confession before baptism of those who came to him, not because he himself needed to know their sins, but so as to effect their salvation. (22)

He goes on:

Eagerly drink scorn and insult as the water of life from everyone who wants to give you the drink that cleanses from lust. (23)

And:

Let the zealous be particularly attentive to themselves, lest by condemning the careless they themselves incur worse condemnation. And I think the reason why Lot was justified was because, though living among such people, he never seems to have condemned them. (25)

Relates his visit to “the Prison,” where brothers went who were especially sorry for their sins, where the penitents wailed non-stop in sackcloth and ashes. He says repentance is giving up material pleasures and showing sorrow for sins. He says one must acquire the repentance of the Harlot in the Gospel, which is done by turning worldly love into love for God.

I saw there some who seemed from their demeanour and their thoughts to be out of their mind. In their great disconsolateness they had become like dumb men in complete darkness, and were insensible to the whole of life. Their minds had already sunk to the very depths of humility, and had burnt up the tears in their eyes with the fire of their despondency.

Others sat thinking and looking on the ground, swaying their heads unceasingly, and roaring and moaning like lions from their inmost heart to their teeth. And some were praying in good hope and asking for complete forgiveness. (30)

Repentance, compunction, and growth in holiness are impossible without a remembrance of death. Holy people fear death, while unrepentant sinners are terrified of it. One monk lived with no fear of death, but after a near death experience locked himself in his cell and lived off bread and water for the remaining 12 years of his life, his last words being that no one who keeps death in remembrance can fall into sin. Noise prevents people in the world from remembering death. Never when mourning for sins, think of God as tender-hearted, but only if on the brink of despair.

More on the importance of mourning our post-baptismal fall, which is washed away by the second baptism of tears of compunction. Paragraphs like the following remind me of the movie “Silence,” since the priest had a certain kind of pride from holiness (although I have issues with that movie):

Our enemies are so wicked that they turn even the mothers of virtues into the mothers of vices, and those things which make for humility, they make into a cause for pride. Frequently the very setting and sight of our dwellings are of a nature to rouse our mind to compunction. Let Jesus, Elijah and John who prayed alone convince you of this. I have often seen tears provoked in cities and crowds to make us think that crowds do us no harm and so draw nearer to the world. For this is the aim of the evil spirits. (43)

Meekness is an immovable state of soul which remains unaffected whether in evil report or in good report, in dishonour or in praise. (44)

He says meekness and humility are the antidote to anger, while greed, lust, or conceit are its cause. He says some are outwardly angry, while more wretched souls feign meekness but on the inside are raving mad.

It is especially idiotic to be mad when alone, which can turn a human into a demon:

When for some reason I was sitting outside a monastery, near the cells of those living in solitude, I heard them fighting by themselves in their cells like caged partridges from bitterness and anger, and leaping at the face of their offender as if he were actually present. And I devoutly advised them not to stay in solitude in case they should be changed from human beings into demons. (43)

This is the first appearance so far of an the illustration of a ladder, saying that “the holy virtues are like Jacob’s ladder, and the unholy vices are like the chains that fell from the chief Apostle Peter” (47).

Remembrance of wrongs is the offspring of anger, which is far from love but close to fornication.

Slander, calumny or judging others is a sure way to ruin. Mourning one’s own sins is a way to fight this temptation, because then you will realize you will not be able to shed enough tears for your own sins in your lifetime, much less dwell on the sins of others.

The door to anger is talkativeness:

Talkativeness is the throne of vainglory on which it loves to show itself and make a display. Talkativeness is a sign of ignorance, a door to slander, a guide to jesting, a servant of falsehood, the ruin of compunction, a creator of despondency, a precursor of sleep, the dissipation of recollection, the abolition of watchfulness, the cooling of ardour, the darkening of prayer.

Deliberate silence is the mother of prayer, a recall from captivity, preservation of fire, a supervisor of thoughts, a watch against enemies, a prison of mourning, a friend of tears, effective remembrance of death, a depicter of punishment, a meddler with judgment, an aid to anguish, an enemy of freedom of speech, a companion of quiet, an opponent of desire to teach, increase of knowledge, a creator of contemplation, unseen progress, secret ascent. (50)

Joking is caused by lying, which is caused by hypocrisy. You can only tell necessary lies like Rahab once you have been cleansed from lying:

He who gives way to lying does so under the pretext of care for others and often regards the destruction of his soul as an act of charity. The inventor of lies makes out that he is an imitator of Rahab, and says that by his own destruction he is effecting the salvation of others.

When we are completely cleansed of lying, then we can resort to it, but only with fear and as occasion demands.

Despondency sounds like boredom how he describes it, such as yawning in prayer or being distracted by footsteps outside.

Despondency is a slackness of soul, a weakening of the mind, neglect of asceticism, hatred of the vow made. It is the blessing of worldlings. It accuses God of being merciless and without love for men. It is being languid in singing psalms, weak in prayer, stubbornly bent on service, resolute in manual labour, indifferent in obedience. (52)

Gluttony is closely associated with fornication, which is what gluttony leads to, in addition to the heightening of lust and impure dreams.

The more you fast, the more natural it becomes for you, because your stomach shrinks, like unused leather bottles. Feeding hunger only begets more hunger, and it strengthens the tongue and its sins. Hunger must be cut off by hunger.

Gluttony also leads to revelry and jesting.

It is important not to rush toward hard fasts like bread and water, which you will not succeed at, but instead take food for health.

Long bit here on how it requires temperance plus humility to conquer unchaste passions, especially “unnatural” things done while alone, of which it is not good even to speak.

Rejecting all pleasure in beauty, even of immaterial things, makes us close to being like angels.

The good Lord shows His great care for us in that the shamelessness of the feminine sex is checked by shyness as with a sort of bit. For if the woman were to run after the man, no flesh would be saved. (63)

He goes on talking about the difficulty of chastity and various levels of consent one gives to impure thoughts, which become more sinful the greater the consent.

Love of money is the worship of idols. It often has need or care as a pretext, but we must “cut out care” to attain to “pure prayer” (66).

Poverty is the resignation of cares, life without anxiety, an unencumbered traveller, alienation from sorrow, fidelity to the commandments. (67)

Poverty requires detachment, whether in times of material prosperity or scarcity, as with Job.

This sounds like hypocrisy and self-righteousness.

He who has lost sensibility is a brainless philosopher, a self-condemned commentator, a self-contradictory windbag, a blind man who teaches others to see. He talks about healing a wound, and does not stop irritating it. He complains of sickness, and does not stop eating what is harmful. He prays against it, and immediately goes and does it. And when he has done it, he is angry with himself; and the wretched man is not ashamed of his own words. ‘I am doing wrong,’ he cries, and eagerly continues to do so. His mouth prays against his passion, and his body struggles for it. He philosophises about death, but he behaves as if he were immortal. He groans over the separation of soul and body, but drowses along as if he were eternal. He talks of temperance and self-control, but he lives for gluttony. He reads about the judgment and begins to smile. He reads about vainglory, and is vainglorious while actually reading. He repeats what he has learnt about vigil, and drops asleep on the spot. He praises prayer, but runs from it as from the plague. He blesses obedience, but he is the first to disobey. He praises detachment, but he is not ashamed to be spiteful and to fight for a rag. When angered he gets bitter, and he is angered again at his bitterness; and he does not feel that after one defeat he is suffering another. Having overeaten he repents, and a little later again gives way to it. He blesses silence, and praises it with a spate of words. He teaches meekness, and during the actual teaching frequently gets angry. Having woken from passion he sighs, and shaking his head, he again yields to passion. He condemns laughter, and lectures on mourning with a smile on his face. Before others he blames himself for being vainglorious, and in blaming himself is only angling for glory for himself. He looks people in the face with passion, and talks about chastity. While frequenting the world, he praises the solitary life, without realizing that he shames himself. He extols almsgivers, and reviles beggars. All the time he is his own accuser, and he does not want to come to his senses–I will not say cannot. (68-9)

Climacus says the temptation to sleep too much, especially snoozing, is a demon, as well as excessive yawning and distractions in morning prayer.

He reiterates something he has said often so far in this book:

It is possible for all to pray with a congregation; for many it is beneficial to pray with a single kindred spirit; solitary prayer is for the very few. (70)

Vigil here means resisting excessive sleep or having to stay distracted to keep awake. I think statements like this one – “Long sleep produces forgetfulness, but vigil purifies the memory.” (71) – seem contrary to our modern experience, which is that everyone is sleep-deprived. We keep a vigil, but not for prayer.

Fear or cowardice comes from pride.

Those who mourn over their sins but are insensible to every other sorrow do not feel cowardice, but the cowardly often have mental breakdowns. And this is natural. For the Lord rightly forsakes the proud that the rest of us may learn not to be puffed up. (72)

He goes on to say:

He who has become the servant of the Lord will fear his Master alone, but he who does not yet fear Him is often afraid of his own shadow. (72)

The sun shines on all alike, and vainglory beams on all activities. For instance, I am vainglorious when I fast, and when I relax the fast in order to be unnoticed I am again vainglorious over my prudence. When well-dressed I am quite overcome by vainglory, and when I put on poor clothes I am vainglorious again. When I talk I am defeated, and when I am silent I am again defeated by it. However I throw this prickly-pear, a spike stands upright. (73)

Refuse honors:

Do not take any notice of [a brother] when he suggests that you should accept a bishopric, or abbacy, or doctorate; for it is difficult to drive away a dog from a butcher’s counter. (74)

Our natural gifts and holy inclinations are nothing to be proud of.

He who asks God for gifts in return for his labours has laid unsure foundations. He who regards himself as a debtor will unexpectedly and suddenly receive riches. (75)

A definition of vainglory is offered:

Abominable vainglory suggests that we should pretend to have some virtue that we do not possess, spurring us on by the text: Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works. (75)

The solution:

The beginning of the conquest of vainglory is the custody of the mouth and love of being dishonoured; the middle stage is a beating back of all known acts of vainglory; and the end (if there is an end to an abyss) consists in trying to behave in the presence of others so that we are humbled without feeling it. (39)

The value of living simply:

Simpler people are not much infected with the poison of vainglory, because vainglory is a loss of simplicity and an insincere way of life. (76)

By pride, one can fall into all the other sins, but by humility he can avoid them all. The saddle of pride is vainglory, so “holy humility and self-accusation” (79) are the weapons to use against it. Spiritual people are visited by devils in the form of a vision of an angel in order to increase their pride.

He talks about the demon of blasphemy who attacks simple and innocent people with thoughts of blasphemy such that they cannot imagine being saved. He assures them it is only the demon and not their own sin, and to say “Get behind me Satan” and not to otherwise regard it. Trying to grapple with it with anything but prayer is like grappling with lightening. Not judging and condemning your neighbor will also prevent blasphemous thoughts.

Meekness is calm in any situation, peaceful or not. It is when a soul is immune from evil thinking, anger, malice, hypocrisy, etc. Meekness gained by toil and repentance is superior to natural meekness, and infinitely so.

Therefore, last of all, having gathered what fell from the lips of those learned and blessed fathers as a dog gathers the crumbs that fall from the table, I too gave my definition of it and said: ‘Humility is a nameless grace in the soul, its name known only to those who have learned it by experience. It is unspeakable wealth, a name and gift from God, for it is said: Learn not from an angel, not from man, and not from a book, but from Me, that is, from Me indwelling, from My illumination and action in you, for I am meek and humble in heart and in thought and in spirit, and your souls shall find rest from conflicts and relief from arguments.’ (83)

Embrace humiliations:

Therefore we should unceasingly condemn and reproach ourselves so as to cast off involuntary sins through voluntary humiliations. Otherwise, if we do not, at our departure we shall certainly be subjected to heavy punishment. (88)

Embrace poverty:

Nothing can so humble the soul as a state of destitution and a beggar’s subsistence. For we only prove to be philosophers and lovers of God when, having the possibility of exaltation, we flee from it irrevocably. (89)

Discernment in beginners is true knowledge of themselves; in intermediate souls it is a spiritual sense that faultlessly distinguishes what is truly good from what is of nature and opposed to it; and in the perfect it is the knowledge which they possess by divine illumination, and which can enlighten with its lamp what is dark in others. Or perhaps, generally speaking, discernment is, and is recognized as, the assured understanding of the divine will on all occasions, in every place and in all matters; and it is only found in those who are pure in heart, and in body and in mouth. (89)

Intentions behind good works matter, because you can have prideful or other bad intentions even while doing good works. And some vices are entangled in the virtues we seek, like gluttony with hospitality, lust with love, cunning with discernment, and laziness with meekness (94).

Natural virtues are given to all men and some even to dumb animals, and they are mercy, love, faith, and hope. Virtues above nature are chastity, freedom from anger, humility, prayer, vigil, fasting, and constant compunction (96).

It is impossible for all to become dispassionate, but it is not impossible for all to be saved and reconciled to God. (97)

On being patient in cultivating virtues:

So let us not be deceived by proud zeal and seek prematurely what will come in its own good time; that is, we should not seek in winter what comes in summer, or at seed time what comes at harvest; because there is a time to sow labours, and a time to reap the unspeakable gifts of grace. Otherwise we shall not receive even in season what is proper to that season. (98)

On being overly familiar with people:

When we see that some love us in the Lord, then we should not allow ourselves to be especially free with them, for nothing is so likely to destroy love and produce hatred as familiarity. (98)

You must mortify your own will to learn God’s will, and you must learn to obey the advice of others even when it goes against your own views.

To waver in one’s judgments and to remain in doubt for a long time without assurance is the sign of an unenlightened and ambitious soul. (100)

There’s this odd story, which seems to say that lying and gossip are OK if done in order to quail impure affections between two people so that they will instead hate each other:

Blessed are the peacemakers. No one will deny this. But I have also seen enemy-makers who are blessed. A certain two developed impure affection for one another. But one of the discerning fathers, a most experienced man, was the means whereby they came to hate each other, by setting one against the other, telling each that he was being slandered by the other. And this wise man by human roguery succeeded in parrying the devil’s malice and in producing hatred by which the impure affection was dissolved. (103)

Some monastics, especially early on or for those learned in secular studies, are instructed by demons in the interpretation of Scripture in order to increase their pride and lead them to heresy and blasphemy (104).

Every man receives their end from God, but “the end of virtue is infinite” (104), because love is infinite, and even the angels progress in it and will do so for all eternity.

God nor the nature he gave us is evil, but we have taken good qualities and turned them to evil ends, such as childbearing to fornication or anger against the serpent to anger against our neighbor (104).

At the end of this chapter, he gives a summary of all previous steps (107).

One of the summary points (number 64 on page 110) caught my attention, because it seems hard to believe sometimes, given all the evil we see even in the Christian world:

Spiritual perception is a property of the soul itself, but sin is a buffeting of perception. Conscious perception produces either the cessation or lessening of evil; and it is the offspring of conscience. And conscience is the word and conviction of our guardian angel given to us from the time of baptism. That is why we find that the unbaptized do not feel such keen pangs of remorse in their soul for their bad deeds. (110)

Not to doubt the grace of baptism, but how is it that some of the baptized can practice such great evil, while some of the unbaptized more or less have and obey a well-formed conscience?

Here he describes solitude as a haven that those still struggling in the battle against their passions need not dwell on for too long. Solitude is power over one’s thoughts and habits, the fleeing from noise, yet able to be at quiet and at peace amid disturbances.

He is speaking here specifically of solitary monks, whose only spiritual help is from angels, versus those monks who live with one or more others.

It is not safe to swim in one’s clothes, nor should a slave of passion touch theology. (112)

He goes on:

Those whose mind has learned true prayer converse with the Lord face to face, as if speaking into the ear of the Emperor. Those who make vocal prayer fall down before Him as if in the presence of the whole senate. But those who live in the world petition the Emperor amidst the clamour of all the crowds. If you have learned the art of prayer scientifically, you cannot fail to know what I have said. (112)

Those who give up their own will to lead a solitary life converse with God face to face and are like the angels. There are, however, conceited reasons why some choose the solitary life.

To be a solitary requires refusing the remembrance of wrongs and embracing rapture towards the Lord and many other virtues uncommon among men.

A small hair disturbs the eye, and a small care ruins solitude; because solitude is the banishment of thoughts and ideas, and the rejection of even laudable cares. (116)

A man named George Arsilaites once told Climacus, “I have noticed that in the morning it is usually the demons of vainglory and concupiscence who make assaults upon us; at midday the demons of despondency, repining and anger; and in the evening, those dung loving tyrants of the wretched stomach!” (116).

Faith is the wing of prayer; without it, my prayer will return again to my bosom. Faith is the unshaken firmness of the soul, unmoved by any adversity. A believer is not one who thinks that God can do everything, but one who believes that he will obtain all things. Faith paves the way for what seems impossible; and the thief proved this for himself. The mother of faith is hardship and an honest heart; the latter makes faith constant, and the former builds it up. Faith is the mother of the solitary; for if he does not believe, how can he practise solitude? (117)

Watch what you say:

When you leave your cell be sparing with your tongue, because it can scatter in a moment the fruits of many labours. (118)

Prayer by reason of its nature is the converse and union of man with God, and by reason of its action upholds the world and brings about reconciliation with God […] (119)

It is the queen of virtues that cries out to us, “Come unto Me all ye that labour and are heavy laden” (119).

To pray we must be “oblivious of wrongs” (119).

On the importance of preparation for prayer:

If we wish to stand before our King and God and converse with Him we must not rush into this without preparation, lest, seeing us from afar without weapons and suitable clothing for those who stand before the King, He should order His servants and slaves to seize us and banish us from His presence and tear up our petitions and throw them in our face. (119)

Prayer must be simple, such as a single word or phrase, and should start with thanksgiving, followed by contrition, followed by petition.

Climacus says “brevity makes for concentration” (120), and the footnotes point out that the word for “brevity” is “monologia” which means “repetition of a single word or phrase.”

God calms the storms in our minds as long as we keep trying to overcome distractions and “shut off your thought within the words of your prayer” (120).

We must not let our minds wonder, when praying or otherwise.

Pray externally even if you are finding trouble focusing, because “the mind often conforms to the body” (121).

Dispassion is refusing to cling to pleasures of the world.

Our Redeemer holds back gifts from thoughtless souls, lest they get what they want and run off, leaving the giver.

Psalmody in a crowded congregation is accompanied by captivity and wandering of thoughts; but in solitude this does not happen. However, those in solitude are liable to be assailed by despondency, whereas in the former the brethren help each other by their zeal. (122)

He goes on:

When you have prayed soberly, you will soon be fighting against fits of temper. For this is what our enemies aim at.

We should always perform every virtue, especially prayer, with great feeling. A soul prays with feeling when it gets the better of temper and anger. (122)

He goes on:

The assurance of every petition becomes evident during prayer. Assurance is loss of doubt. Assurance is sure proof of the unprovable. (122)

The same fire that purifies us in prayer also becomes eventually “the light which illuminates” (123).

Ask with tears, seek with obedience, knock with patience. (123)

Climacus says one must not overdo praying for the opposite sex nor “go into detail when confessing physical acts lest you become a traitor to yourself” (123).

Don’t be thinking of things you need to do during prayer (124).

Close of this step:

Have all courage, and you will have God for your teacher in prayer. Just as it is impossible to learn to see by word of mouth because seeing depends on one’s own natural sight, so it is impossible to realize the beauty of prayer from the teaching of others. Prayer has a Teacher all its own – God – who teaches man knowledge, and grants the prayer of him who prays, and blesses the years of the just. Amen. (124)

Dispassion is regarding the tricks of the demons as mere toys and raising the mind to God in such a way as to rise above creatures and subdue the senses. It is said to be like being in heaven on earth (124-5).

He has a long paragraph of comparisons to vices and their dispassionate opposites, such as:

If it is called a sea of wrath for a person to be savage even when no one is about, then it will be a sea of long-suffering to be as calm in the presence of your slanderer as in his absence. (125)

He has a beautiful paragraph comparing the heavenly kingdom to a great palace with smaller mansions as successively smaller virtues, and if we cannot at least scale the outer walls (the smallest virtues) of the kingdom, we will be in hell (126).

Blessed dispassion raises our minds to heaven, but love makes us sit with princes and angels (126).

Faith, hope and love are compared to the rays of the Sun, it’s light, and it’s “circle” (as in, circuit), because the first creates, the second is immune to disappointment by divine mercy, and the third never stops along it’s course (126).

But to speak of love is to speak of God himself (126).

Love is closely related to dispassion. “As love wanes, fear appears; because he who has no fear is either filled with love or dead in soul” (127).

Even a mother does not so cling to the babe at her breast as a son of love clings to the Lord at all times. (127)

He goes on:

He who truly loves ever keeps in his imagination the face of his beloved, and there embraces it tenderly. Such a man can get no relief from his strong desire even in sleep, even then he holds converse with his loved one. So it is with our bodily nature; and so it is in spirit. One who was wounded with love said of himself (I wonder at it): I sleep because nature requires this, but my heart is awake in the abundance of my love. (127)

When we are entirely in love with God, we become a shining mirror of his love and splendor, as when Moses descended Mount Sinai with a shining face (127).

I think that the body of those incorruptible men is not even subject to sickness any longer, because it has been rendered incorruptible; for they have purified the inflammable flesh in the flame of purity. I think that even the food that is set before them they accept without any pleasure. For there is an underground stream that nourishes the root of a plant, and their souls too are sustained by a celestial fire. (128)

It is impossible to love and be angry at the same time (128).

“Love is the state of angels. Love is the progress of eternity” (129).

He ends this step with the following reflection:

Tell us, fairest of virtues, where thou feedest thy flock, where thou restest at noon. Enlighten us, quench our thirst, guide us, take us by the hand; for we wish at last to soar to thee. Thou rulest over all. And now thou hast ravished my soul. I cannot contain thy flame. So I will go forward praising thee. Thou rulest the power of the sea, and stillest the surge of its waves and puttest it to death. Thou hast humbled the proud–the proud thought–like a wounded man. With the arm of thy power thou hast scattered thy enemies, and thou hast made thy lovers invincible.

But I long to know how Jacob saw thee fixed above the ladder. Satisfy my desire, tell me, What are the means of such an ascent? What the manner, what the law that joins together the steps which thy lover sets as an ascent in his heart? I thirst to know the number of those steps, and the time needed for the ascent. He who knows the struggle and the vision has told us of the guides. But he would not, or rather, he could not, enlighten us any further.

And this queen (or I think I might more properly say king), as if appearing to me from heaven and as if speaking in the ear of my soul, said: Unless, beloved, you renounce your gross flesh, you cannot know my beauty. May this ladder teach you the spiritual combination of the virtues. On the top of it I have established myself, as my great initiate said: And now there remain faith, hope, love–these three; but the greatest of all is love. (129)

And he ends the book with a brief exhortation and summary:

Ascend, brothers, ascend eagerly, and be resolved in your hearts to ascend and hear Him who says: Come and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord and to the house of our God, who makes our feet like hind’s feet, and sets us on high places, that we may be victorious with His song.

Run, I beseech you, with him who said: Let us hasten until we attain to the unity of faith and of the knowledge of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ, who, when He was baptized in the thirtieth year of His visible age, attained the thirtieth step in the spiritual ladder; since God is indeed love, to whom be praise, dominion, power, in whom is and was and will be the cause of all goodness throughout infinite ages. Amen. (129)

Climacus, John. The Ladder of Divine Ascent. Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, Harper & Brothers, 1959, www.prudencetrue.com.... Accessed 6 Sept. 2021 ↩

Pope Benedict XVI. “General Audience: Paul VI Audience Hall Wednesday, 11 February 2009.” Vatican: the Holy See. Vatican Website. Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2009. Web. 4 July 2022. ↩